Today’s building automation technology: why is it so complex, bureaucratic and expensive?

Considering how automated many artificial environments are, it is remarkable that most buildings today have so many manual controls.

Contrast any large building that you know with a modern executive car. Before you even open the door, the car knows that you are near and releases the locks. As you step in, the interior lights turn on automatically. The car knows the temperature inside and out, and adjusts the HVAC fans and heaters automatically. The car also knows how many people are inside, and whether they are safely restrained or not.

Fig. 1: the interior of the latest BMW 5 Series car, a highly automated environment. (Image credit: BMW)

Contrast that with most buildings you know: you will have to manually turn lights on, manually adjust the heating and air-conditioning controls in each room, and manually turn everything off if you know a room is to be unoccupied.

In a world full of computers and network infrastructure, this is ridiculously low-tech. So what’s stopping buildings from becoming smarter? If a car can automate the systems that keep the driver and passengers comfortable and safe, why can’t a building?

The surprising answer: bureaucracy. Not human bureaucracy, the type that can make governments and large companies intensely frustrating to deal with, but technical bureaucracy.

Today’s Building Automation Technology: too many protocols, layers and adapters

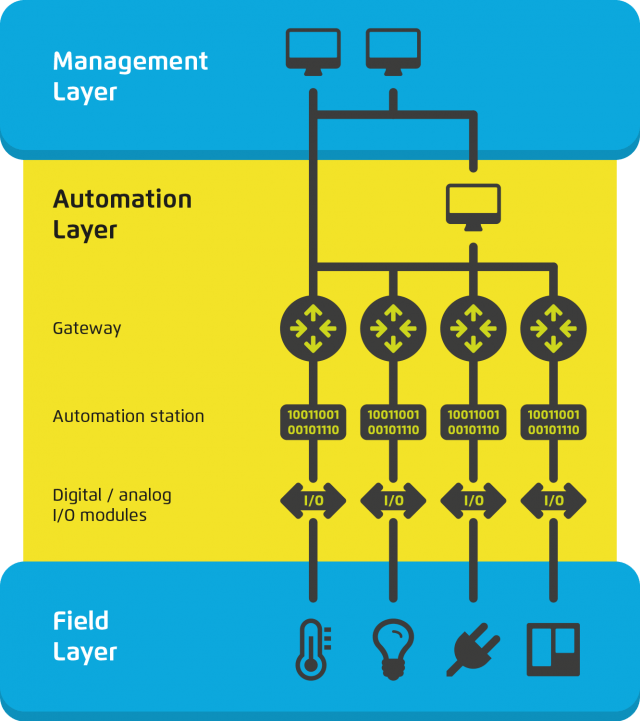

The truth is that building automation systems today are complex and inflexible. They generally require every single field device – each boiler, radiator, air-conditioning unit, door lock and luminaire – to connect to a central control unit. The architecture is often something like that shown in Figure 2.

The various device types often use different protocols for communication, so multiple layers of interconnections are required to get a common set of signals in and out of the control unit. It’s like the worst example of bureaucracy in an office. It’s as though a small team of office workers in a subsidiary office of a large organisation employing thousands of workers have to get the CEO’s permission every time they need to order a new batch of printer paper.

And the CEO handles paper purchase requests from hundreds of branch offices in various countries, so each request has to be translated into the CEO’s mother tongue before it can be processed. Such a bureaucracy would be insanely slow, expensive and frustrating. And yet that is how today’s building automation technology is configured.

Fig. 2: building automation systems today involve multiple layers, standards, protocols and interconnections

It’s expensive, because it requires so many I/O devices, gateways and controllers operating with so many different protocols. The infrastructure for wiring these many devices together is slow and expensive to install. The system is inflexible, because once the building operators have gone to the effort of connecting existing devices together, they are loath to change the configuration or to add new devices.

And as a result, operators can often find themselves tied to a single supplier which guards the knowledge about the complex technology required to make so many disparate protocols and standards interoperate.

But why does it need to be so complex?

What if an infrared proximity sensor in a room wants to tell a light switch in the same room to turn on a light in the same room, because it has detected that a person has entered this same room? Why should a building automation system make this simple instruction go all the way to a remote central control unit and back?

Instead of maintaining a large and complex bureaucracy to make buildings comfortable, safe and convenient, why can we not figure out a way to do Lean Building Automation?

In a second article we’ll talk about how to reduce complexity and make Building Automation Lean. Check back soon!